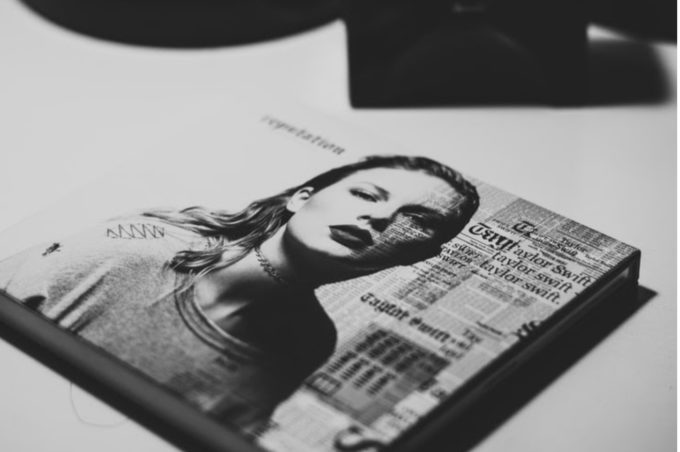

Never in my wildest dreams would I have thought that someone other than Taylor Swift owns Taylor Swift’s songs. But it’s true and poses a hurdle as Swift commits to re-recording her own songs. This delicate situation has led to some bad blood between Swift and Scooter Braun, who owns the rights to the master recordings of Swift’s older music.

Unknown artists like (believe it or not) Swift in 2008 sign record deals that exchange promotion for copyright ownership. Each song carries two kinds of copyright: the substance of the song itself (including its composition, musical arrangement, and lyrics) and the transferability of the recording. Song writers own the substance of the song. Luckily for Swift, she writes her own songs, so there is no copyright issue with reusing her own lyrics or instrumentals. Though, record companies generate a physical master record once a song is recorded. This record is more than just a symbolic homage to the past during the digital age of music streaming services. It carries transferability rights, namely the right to use a copy of the song. For Swift’s earlier albums, these rights originally belonged to Big Machine Records, but were transferred to Braun when his company, Ithaca Holdings, purchased Big Machine.

Although Swift recently signed a deal with Universal Music Group (“UMG”) giving her ownership of any new master records she records with them, it does not apply retroactively to the master records belonging to Big Machine. Braun still owns the copyright to Swift’s older songs and still earns licensing fees any time a TV show, streaming service, or movie uses them, and more importantly to Swift, he still possesses the ability to determine who uses them. After a public falling out with Braun over an attempt to regain control of her own music, Swift developed a plan that might be better than revenge.

A provision in Swift’s contract with Big Machine Records said she was allowed to re-record her own songs starting November 2020, so Swift has committed to it. That way, Swift can own new master recordings, because of her contract with UMG, and essentially create a cover of her own songs. Copyright ownership will therefore give her some control over who uses her re-recorded music, and she can collect royalties from licenses to the re-recorded music.

Does this mean everything’s changed for Swift, and can she cast Braun and his copies of her master recordings into exile? Not quite. Braun has a strong incentive not to shake it off, and Swift’s old master records won’t disappear as she releases new ones. If Swift refuses to license her re-recording to someone, they can always turn to Braun. Also, anyone who wants a license to a Swift song now is situated in a competitive market; they can trigger an “inverse bidding war” and get a license from whoever will offer it for the cheapest price. Because the process could devalue her own music and not result in much more control of it, re-recording her music was a gamble. That could have Taylor saying (Blank Space)!

Swift is not out of the woods yet; we still have yet to see what will happen once Swift re-records her own songs. She may be successful in taking away revenue from Braun and exercising full control of her old music. Although Swift has been advocating for artist control over their own master recordings, up-and-coming artists lack the negotiation power to get such a favorable contract like that between Swift and UMG. But Swift could ultimately inspire more popular artists to leverage their fame and restructure their contracts to get similar provisions guaranteeing greater control over their creative work.