Geofence Searches Are Not (Necessarily) Carpenter Searches

By Pedro Silva - Edited By Shriya Srikanth

Pedro Silva received a J.D. from Harvard Law School, where he was the Notes and Comments editor for the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology. Before law school, Pedro was a software engineer at Google developing cloud cryptography systems. He graduated from Northeastern University with a degree in Computer Science and Mathematics. His writing focuses on how technology is shaping constitutional law, privacy, and jurisprudence.

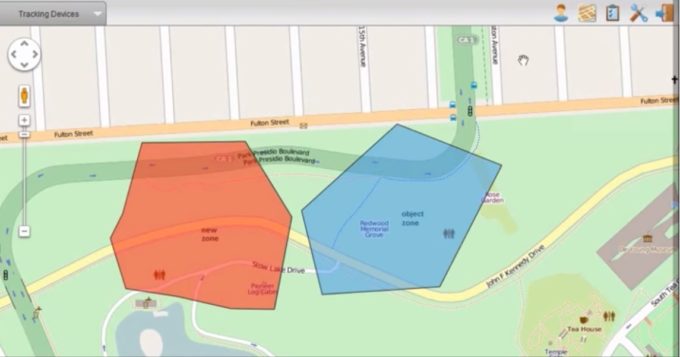

Over the last year, the Fourth and Fifth Circuits have created a split over the legality of geofence warrants—the kind that allows police officers to collect the identifying information from any phone that was located within a certain place at a certain time from companies like Google. Some commentators have suggested the question was already answered by United States v. Carpenter, which held that police needed a warrant to collect location data on a suspect. However, a close inquiry into the technical details of the steps computers take in these searches reveal significant differences that suggest that geofence searches are not (necessarily) Carpenter searches. Instead, as argued below, a closer examination of how these searches actually take place in the computers will often reveal that often, a series of additional steps by computer programs, possibly presenting new constitutional questions which courts will need to address.

Recent Caselaw

After ample discussion among public interest groups, and a pass from the Colorado Supreme Court, federal appellate courts have finally begun to evaluate the constitutionality of geofence searches. On one side, the Fourth Circuit first held in United States v. Chatrie that the Fourth Amendment did not prohibit the geofence searches, and that a warrant was not required. On the other hand, the Fifth Circuit then held in United States v. Jamaar Smith that these kinds of requests are categorically a violation of the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches. The Fourth Circuit decision is now under en banc review.

In a simplified set up, the questions for courts evaluating geofence warrants are, effectively: (1) does a geofence search compelled by the police constitute a “search” as specified by the Fourth Amendment? And (2) if the answer to (1) is “yes,” do warrants based only on a certain location and time period fail to be “particular” enough?

The Fourth Circuit decided in Chatrie that the answer to the first question was “no.” Geofence searches, according to the court, do not involve “searches” in the Fourth Amendment sense. The court relied on the third-party doctrine, where the Supreme Court has held in a series of cases that certain kinds of information shared by individuals with third parties may be gathered by the government without a warrant. Specifically, the Chatrie majority pointed out that the warrant implicated privacy concerns only to a limited degree and that the defendant had voluntarily shared the information with Google. Thus, to the extent Google and the police went through Google’s user records, there was no “search” in the Fourth Amendment sense.

The Fifth Circuit disagreed. Dealing with similar facts for a geofence warrant, the panel decided that the answer to both questions were “yes.” It first determined that the warrant involved a search. Acknowledging the Fourth Circuit’s view that the warrant was limited in operation, the Fifth Circuit highlighted that “the potential intrusiveness of even a snapshot of precise location data should not be understated.” And while it recognized that Smith had voluntarily shared his location data, the majority pointed out that “electronic opt-in processes are hardly informed and, in many instances, may not even be voluntary.” The Smith court further pointed out that when Google is served with a geofence warrant, it must first comb through its database of 592 million people to determine which ones were in the time and place described by the warrant.

Who’s right? The Fourth Circuit, says Professor Orin Kerr, in a post for The Volokh Conspiracy. Even if the Fourth Circuit is incorrect, Kerr argues, the Fifth Circuit is still wrong. As Kerr would see it, even if a geofence reverse search does involve a “search” in the Fourth Amendment sense, the geofence warrants are sufficiently particular. The Supreme Court has not provided an answer so far.

What About Carpenter?

Both courts amply discussed the 2018 Supreme Court case United States v. Carpenter. In that case, the government had obtained, without a warrant, Carpenter’s location data from his phone service provider. The Supreme Court ruled that practice unconstitutional. It rejected the third-party doctrine application, as it ruled that Carpenter had a legitimate privacy interest in his location and that he had not expressly agreed to share his location data. Thus, a subpoena was insufficient, and a warrant was required.

There are many differences between the facts in Carpenter and Smith. But one way to frame the Court’s holding is that a warrant is the correct manner to access location data from service providers. Under that framing, the seemingly necessary implication is that a warrant is not just required, but also sufficient to request a suspect’s location records stored with a third-party provider. In other words, the Supreme Court may have outlined in Carpenter how officers should go about obtaining location data on someone — get a warrant. Indeed, Professor Kerr relied on that reasoning in order to conclude that the Fifth Circuit was wrong:

Carpenter obviously contemplates warrants for non-content user account records. That was the whole premise of the Carpenter's warrant ruling. The Supreme Court, faced with a decision about what level of protection the Fourth Amendment requires, picked the warrant rule over the subpoena rule. . . . The nature of the Carpenter ruling is that queries for Carpenter-protected records will generally be through massive databases. Under the Fifth Circuit's decision, however, the Supreme Court's warrant holding in Carpenter was basically meaningless. Most searches for Carpenter-protected data will be through massive databases.

But even if the data and the service providers are similar, not all searches are the same. As the ACLU (which represented Smith) has responded to Professor Kerr, the warrant that initiated the search presents a primary difference, since one targets a single person and the other targets a location:

[T]there is very little in common between the targeted query pulling up one suspect's records in Carpenter, and the dragnet search for anyone whose phone was in or near a 24-acre area in Smith. Police can ask an email provider to turn over a particular person's messages with a valid warrant, but that doesn't mean police can direct the company to search through every email of every user in the hope of finding someone who was discussing a crime.

This essay expands on why the ACLU’s argument is likely correct, especially as it relates to the computer’s step-by-step.

Carpenter vs. Geofence Searches

A key distinction between Carpenter searches and geofence ones is in the technical details. Before describing each one, some review of how database searches take place is helpful.

In many ways, a great number of databases used in commercial activity are the kind which, in the simplest terms and for the purposes of this discussion, work through “tables” resembling 2x2 spreadsheets. When creating such a table, various data fields are defined as “columns” for the different kinds of data, and one particular column is the “index” which provides a unique identifier for the rows. Then, each “cell” contains the value for a particular row identifier and a column’s kind of data.

In his response to the ACLU, Professor Kerr offered an example: what if one were searching a database containing email files? The table could be represented in a 2x2 matrix, with columns for an identifying “file #”, the sender’s identity, the receiver’s identity, the date the message was sent, and another for the contents. (Relying again on Professor Kerr’s example, here is a link to a visualization.)

As Professor Kerr points out, searching through this database can be as simple as going through every email and deciding whether that email fits a particular criterion: whether that be the account value of the sender or the words used in the content.

So isn’t it all the same thing?

Not quite. If this were how Google searches emails, that would mean that any time a user logs into Gmail, Google must comb through every single email in its database, filtering for the right email address in every email’s “to,” “from,” “cc,” and “bcc” lines. With millions of users accessing the service at every hour, each with a very high amount of emails each, the search would be a painfully slow process, even for a company with the resources of Google.

Instead, databases allow software developers to “index” on the basis of unique identifiers. In this case, something like the account address could serve as a unique starting point within the system. In oversimplified terms, indexing allows computers to turn a unique value like one’s email address into an actual “computer address” for where some information is stored in a highly efficient manner. This way, rather than Google having to comb through every email including every user for, say, pedro@jolt.harvard.edu, Google can simply convert “pedro@jolt.harvard.edu” into a “computer address” and structure the database to use the resulting computer address as the location of where to both store and collect the emails relating to that account. When the bookstore sends an email to pedro@jolt.harvard.edu about the latest book sale, the email goes into the part of the database identified by the appropriate “computer address," rather than a main pile with all Gmail’s emails.

In pseudocode and computer science terms, this means going from an O(N) solution (where the algorithm’s worst-case runtime grows linearly),

for email in all_emails_in_server:

if fits_search_criteria(email):

results.append(email)

return results

to a far more efficient O(1) solution (where the algorithm’s worst-case runtime is constant),

return emails_keyed_by_users(turn_into_computer_address(email))

An analogy with an overburdened metaphor in criminal procedure may be helpful. Imagine you found yourself in a parking lot full of cars, and someone had asked you to find a certain box they left in their car’s passenger seat. In scenario A, imagine that’s all they gave you: you would need to look through the passenger window of every car in the parking lot, and take note of every car that contains a box in their passenger seat. In scenario B, imagine they gave you the key to the car: you press the button to lock it, prompting the right car to identify itself through lights and sounds; you recognize it instantly, and go directly to it. Sure, you could theoretically still go car-by-car with the other information. But by having a key, whose signal is unique in the parking lot, you can go directly to the right car. And the result might all be the same: you might find that only one car had the box in the seat. Yet the search steps—particularly as they relate to the other cars—are very different. In scenario A, the number of cars you peer into is, at worst, all cars in the parking lot. In scenario B, the number of cars you peer into is always one. [1]

This is all a bit of what service providers are doing. In searches like the one in Carpenter, the system goes directly to the right “row,” and the information of the specified individual (and only the individual) is retrieved and examined. The warrant’s way of specifying the information (the identifier for a single individual) happens to be a suitable basis for Google’s service to optimize around. In searches like the ones from geofence warrants, however, the service providers must investigate every account in order to find a match.

Could it be different?

A worthy caveat to make is this differentiation is not necessarily the case. Locations, of course, are also unique, and thus could be the basis for indexing as well. Hypothetically, Google could use coordinates like longitude and latitude, or even simply addresses, for its “index” and retrieve users per location. Indeed, Google itself has attempted to standardize unique identifiers for different locations on the globe.

But this has not been presented to courts and—though this is speculative—such a database system is an unlikely implementation: from what is known about the systems used in geofence searches, such as the one reviewed by the Fifth Circuit, all services start with the user first, and each user’s data includes a series of locations and timestamps. Google’s service is designing around a user knowing where they have been, not around users knowing who has been in a location. One could conceive of scenarios where the location is the starting point, but absent additional information, that is not Google’s service in question. It so happens that the identifying information in the Carpenter warrant (the unique identifier of a user) is a far more common indexing basis than the information in the geofence warrants (time and place identifiers).

Of course, Google could build a location-first service, and there may be an interesting question as to whether the government could compel that effort to improve its legal case. That’s for another essay.

Conclusion

With this distinction in mind, Carpenter no longer seems to clearly demand a particular result for courts evaluating the constitutionality of geofence warrants, even if read to suggest that warrants are both required and sufficient for the data it concerned. Not only are geofence warrants different from the one in Carpenter, the searches that these warrants demand—the actual steps taken by the computer—constitute a different interaction with the data of the other users in the database.

[1] A reader may here protest by stating that looking into the cars is not a Fourth Amendment “search,” so not additional “searches” take place in scenario A. Even if so, the critical difference is the additional steps—and whether these additional steps themselves constitute searches. In both the example and in the case of geofence searches, the answer might be “no,” but the need for additional consideration for those steps makes geofences searches very distinct from the one in Carpenter.