Kevin Frazier directs the AI Innovation and Law Program at the University of Texas School of Law and is a Senior Fellow at the Abundance Institute.

Introduction

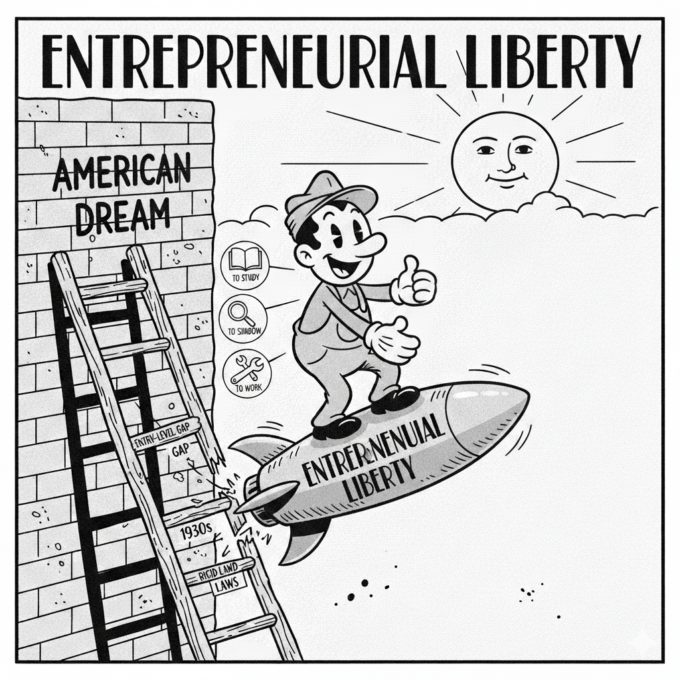

The American Dream is unattainable for too many hard-working men and women. It's not for lack of effort, will, or talent and it’s not solely because of artificial intelligence. [1] Other factors are much more to blame. Congress must avoid the temptation to overreact to AI—the latest but not last general purpose technology (GPT) to introduce economic uncertainty—and should practice good governance by prioritizing foundational issues. The focus of this essay is on a select set of structural reasons for why so many Americans feel stuck and outlines three principles to guide legal reforms that will revive and sustain the American Dream. Absent such reforms, the “dream of a better, richer and happier life for all our citizens of every rank” will continue to go unrealized. [2]

Rigid laws that create pervasive incentives explain why Americans are struggling to get ahead and stay ahead amid technological change. In prior eras, Congress made adjusted educational and professional pathways to success in response to that era’s GPT. [3] What’s different now is the fervent defense of the status quo—as if the jobs of today will and must persist. [4] There’s a reason you cannot find op-eds about the need to defend “horse pooper scoopers”—trust me, I’ve looked through The New York Times’ archives. America’s economic success has been and will be a product of our willingness to be the first to the future rather than the last to move on from the past.

AI should not be treated as a scapegoat for the high rate of entry-level unemployment nor as the bogeyman behind every negative economic headline. [5] While the generative AI tools in use today are new, the economic effects are compounding trends that were underway before ChatGPT [6]—increased demand and supply of alternative work arrangements, the need for modular educational opportunities, and the shortage of vetted training positions.

Congress must oversee an overdue transition from regulations created in the 1930s based on technologies from the 1920s to ensure all Americans enjoy Entrepreneurial Liberty—to study at institutions that align with their values, career goals, and schedule; to shadow a mentor in an emerging field; and, to work the job or jobs that align with their skill set and financial aims. [7]

In short, the pathways to the American Dream are broken. Congress can restore them by following three principles. First, if it doesn’t work, don’t fund it. Myriad reports have shown that federal retraining programs are ineffective, duplicative, and wasteful. [8] Whether Congress continues to fund existing or new programs should be contingent on rigorous assessment of their efficacy.

Second, there’s no one right answer to empowering Americans to thrive in the Age of AI but there are many wrong ones. Rather than rush to regulate, Congress ought to err on the side of experimentation. Sunset clauses, regulatory sandboxes, regulatory holidays, and sunrise clauses are examples of the many tools that Congress can lean on to avoid today’s bad laws from becoming tomorrow’s near-permanent barriers. [9]

Third, if it’s a barrier to any aspect of Entrepreneurial Liberty—to study, to shadow, or to do as Americans deem fit—reform it or, better yet, remove it. Creation of a vocational training exception that allows Americans to more easily make withdrawals from individual retirement accounts, such as Trump Accounts and 529 plans, is a good place to start. [10]

The remainder of this essay proceeds in two parts. The first part provides a brief overview of the relationship between Entrepreneurial Liberty and the American Dream. The second part further describes the freedoms associated with entrepreneurial liberty—to study, to shadow, and to work.

The American Dream and Entrepreneurial Liberty

The American Dream is well-known but rarely precisely defined. Specification of its terms and goals is important at a time when policymakers are rightfully concerned about the ability of Americans to secure a better life for themselves and their loved ones. James Truslow Adams coined the phrase in his 1931 book, The Epic of America. He described it as “a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.” [11]

Contemporary officials have adopted and expounded upon Adams’s definition. President Donald J. Trump, for instance, has championed the idea of an “ownership society.” [12] This framing has received bipartisan support for several years, if not decades, and generally refers to the idea of “personal responsibility, possessive individualism and self-reliance” [13]. President George W. Bush also touted an “ownership society,” [14] and explicitly tied the concept back to the American Dream [15]. On the other side of the political spectrum, policies related to “self-sufficiency” [16] or “economic security” have been proposed to assist Americans in their pursuit of the Dream. [17] Across these different, yet connected interpretations, the Dream evokes the possibility of improving upon your family’s station—making progress in domains ranging from education credentials to professional milestones. [18]

By any one of the commonly accepted measures of the American Dream, empirical analysis reveals it is in increasingly short supply. [19] Fewer and fewer Americans go on to earn more than their parents [20]. In fact, nearly one in five young adults live with their parents. [21] Worse yet, an increasingly large share of Americans find themselves in financial peril [22]—unable to take the sorts of risks and make the sorts of investments that are associated with American ingenuity.

The elusiveness of the American Dream did not happen by accident. Deliberate policy choices have contributed to its decline. That’s precisely why Congress must recognize and prioritize Entrepreneurial Liberty and its three tenets.

The Three Freedoms of Entrepreneurial Liberty

Entrepreneurial Liberty—expressed by the three tenets detailed below—is a prerequisite for the American Dream. Realization of the freedom to study, shadow, and work will allow more Americans to achieve economic security and exercise liberty—national goals since 1776.

Freedom to Study

A commitment to advancing the core tenets of Entrepreneurial Liberty would set Congress on the proper policy path at a time when the American people need a federal response to changing and, for many, challenging economic conditions.

The first tenet is ongoing opportunities to study both the foundations of what makes for a good citizen in a republic—critical thinking, literacy, statistics, interpersonal skills—and the underpinnings of the fields of the future—those that require “know what” (think exercising judgment and applying lessons learned through experience) rather than merely “know how” (think completion of rote tasks) that AI can easily automate. [23] Policies aligned with this tenet will make it possible for more Americans to have a wide range of affordable, high-quality, and modular educational opportunities. These sorts of policies are especially necessary when a new general purpose technology, such as electricity or the Internet, emerges.

The same is especially true in the Age of AI. This technology is altering both how we can learn and what we need to learn to flourish in our personal and professional capacities. Now’s the time to critically examine how our education systems can be reformed to meet the needs of young and old Americans alike. This moment of transformation presents us with a chance to identify and do away with tired institutional assumptions and norms. For instance, given all of the evidence detailing the learning losses that transpire during the summer [24], it’s worth studying what’s required to provide young Americans with a school calendar tailored to the Intelligence Era, not the Agricultural Era. [25]

Holistic educational reforms in line with Entrepreneurial Liberty should and must span from pre-K to near-AARP membership. At the K-12 level, parents should have a chance to enroll their students in schools tailored to different skill sets, beliefs, and curriculums, such as charter schools that lean into AI or even micro-schools, akin to those that popped up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Implementation of the OBBB’s tax credit for donations to ‘scholarship granting organizations’ (SGOs) in 2027 will make a big difference for many families currently unable to afford their preferred option. [26] However, the likely effectiveness of SGOs is unclear. States may opt not to recognize SGOs or may only recognize SGOs that plan to support specific kinds of schools. [27] It’s likely that additional levers will need to be pulled to facilitate the introduction of new kinds of schools with new curriculums and varied approaches to using and teaching AI.

At the high school level, this should look like students again having a diversity of offerings in terms of curriculum, schedule, level and nature of AI exposure, and inclusion of practical learning experiences, such as internships and apprenticeships. It may also be worth challenging the idea that all students should be expected to maintain continuous enrollment in formal educational settings. [28] Certain students may benefit from prolonged leaves of absence or work releases for unique vocational opportunities [29].How best to allow for these ‘practical sabbaticals’ is another topic that merits ongoing study.

Beyond high school, there’s an even greater need for flexibility. Many four-year programs and community colleges have long operated at a distance from the private sector. [30] For some programs, this distance may be demanded by the nature of the subject, such as psychology. In other fields, however, a disconnect between private firms and educational experiences is cause for alarm. Students may be spending valuable time and scarce resources out of an expectation that they will be ready to step into a job upon graduation—of course, private firms hope for such an outcome. Yet, poor communication between innovators and educators may result in students learning the wrong skills and practices. There’s tremendous room for improvement when it comes to involving the private sector in developing curriculums and designing evaluations.

Freedom to Shadow

Improved classroom experiences alone will not meaningfully advance Entrepreneurial Liberty and, by extension, the American Dream, if it is not paired with the sort of practical education necessary to add value in the private sector. Provision of this practical education by way of apprenticeships will not be easy but is far from a political pipedream. Apprenticeships used to be a far more common way of learning a trade in the United States . [31] The formalization of education and creation of specific guilds with various licensing requirements theoretically made apprenticeships less necessary by creating alternative pipelines to careers in those industries. In practice, it’s becoming less and less clear that such educational programs serve as a viable substitute for the hands-on training afforded by apprenticeships. [32]

States more committed to broad reforms—allowing students real chances to partner with industry stakeholders and learn the skills most relevant to an emerging field—demonstrate the shortcomings of "experiential learning” done in the classroom. True experiential learning requires substantial investment in both the proper facilities and relationships with the appropriate stakeholders.

Two examples make this point clear. Students at Middleton High School in Wisconsin can get true hands-on experience in mechanical fields that have gone “overlooked” in the digital age. [33] Thanks to a $90 million dollar investment in new facilities, Middleton students are preparing to become the next generation of ironworkers and boilermakers. [34] Similarly, students enrolled at a P-TECH institution have extensive opportunities to develop and apply practical knowledge. P-TECH institutions span from grades 9 to 14 and involve a high school, community college, and corporate partner. The trio collaborate to set forth “an academically rigorous and economically relevant curriculum.” [35] Graduates earn both a high school diploma as well as a two-year associate degree—while also leaving with skills in high-demand in the surrounding area. [36] While experiential programs vary in rigor, quality, and relevance to the tasks or profession in question, they are generally imperfect substitutes for true shadowing experiences.

Other countries have managed to have greater success when it comes to setting up apprenticeship programs. Dual-track programs in Germany are a commonly cited case study of how to provide students with substantive professional experiences while also taking on traditional courses. [37] While some aspects of that approach are unlikely to translate to a U.S. context, they stand as proof that the status quo for most Americans need not be the standard approach going forward.

Congress ought to vigorously pursue policies that afford more Americans the sort of training that employers actually seek. Progress on this front looks like more Americans having more opportunities at an earlier age and throughout their professional careers to participate in formal professional training as an apprentice, intern, or some other arrangement that involves explicit training and guidance. Ideally, such programs will also feature evaluations of skills that can be added to the participant’s formal transcript and CV. [38] A move toward this sort of tracking—mastery of specific skills and tasks—will help educators determine whether a student needs to take certain courses and employers make hiring decisions based on more reliable signals than grades.

Success on this front would go a long way toward maintaining and spreading the American Dream. To the extent individuals struggle to find the formal educational opportunities right for their learning style and values, substitute means to convey an interest in and mastery of a relevant topic can open myriad doors.

Shadowing programs—be they internships, apprenticeships, or a hybrid—are all the more necessary in the Age of AI. The likely elimination of certain entry-level positions as a result of AI taking over a larger share of tasks typically assigned to those workers may remove rungs in the career ladder of many professions. [39] Put differently, as the demand for junior roles shrinks, recent graduates or new members of a field will find it harder to get their foot in the door and, perhaps even more importantly, to develop the skills necessary to move into roles that require wisdom and judgment.

The legal profession is a great example of this talent pipeline phenomenon. [40] There’s been a decline in the number of junior associate roles. [41] These positions come with long hours, high expectations, and, consequently, regular and formative meetings with more senior attorneys. It is time spent in these roles that have traditionally provided junior lawyers with the time to pick up best practices. There are few ways to gain such skills absent prolonged and diverse exposure to the relevant tasks and problems. Individual firms, however, may not have the necessary incentives to provide such basic training if it's unlikely that the worker will stick around. [42] There’s also the issue of many more senior people not having the disposition, skills, or career incentives to invest in providing such training. [43]

These dynamics play out in other fields, too. So something has got to give if young Americans are going to find a way to professional success. The policy prescriptions here mark a strong starting point—they each promise to either increase the availability of younger Americans to take on apprenticeships or to spur employers to offer more trainee positions. Yet, creation of a strong apprenticeship policy framework does not resolve the question of whether Americans can then go on to earn a secure income. Many apprentices end up working in different fields or simply drop out of the program. [44] If it’s assumed that these fields also have some degree of exposure to AI, then Congress must also address the freedom to work. This legislative agenda entails reforming outdated laws so that people can take on the job or jobs that align with an individual’s skills and goals and to earn an adequate living while doing so.

Freedom to Work

Not all work is created equal under existing labor laws, tax provisions, and benefits packages. The same task performed by two different people carries the same value to the end recipient, yet those individuals may receive different kinds and amounts of compensation . This reality stands out as particularly un-American given the insistence of the Founders on the value of economic independence, of entrepreneurial energy, and of small businesses [45]—a belief that has generally found at least some support over the course of every subsequent generation. [46]

Celebration of the little guy, the pioneer, and self-starter is as American as apple pie and is enshrined in other parts of our legal system. Patents aim to spark individual creation. Bankruptcy laws permit Americans to meaningfully start over if their first venture flounders. Flexible arrangements for investors to back founders make the U.S. the best place to have a good idea and the home to more leading AI firms than any other nation. Yet, for reasons that are better explained elsewhere, Americans are now very strongly steered toward specific types of employment.

The Freedom to Work calls on Congress to develop policies that do not force Americans to choose between the legal form of their work and the benefits that derive from that work. [47] This is far from the first time Congress has faced such pressures. [48] Many have called for alternative work arrangements to be more easily adopted by workers and employers [49], for tax simplicity and clarity [50], and for portable benefits [51]. If formalized into policy, Americans could generate more income from more skills and do so with greater flexibility and autonomy.

The positive benefits would not end there. Parents are especially likely to participate in alternative work arrangements—for obvious reasons, increased flexibility makes it easier for people to start or grow their families. Justified concern about diminished birthrates have led to innovative and necessary policies at the state and federal level. The freedom to work represents another tangible step to encourage more Americans to launch families (in addition to side hustles and startups).

Furthermore, the creative projects launched under the freedom to work may be the seeds that blossom into the next best example of America’s economic and entrepreneurial might. There’s a reason that Google often permits its employees to pursue so-called “twenty percent projects.” [52] Under this scheme, employees may spend up to a fifth of their working hours on an approved side project. [53] Most Americans do not have subsidized nor compensated time to tinker with their latest idea. The freedom to work would not be as generous as a twenty-percent project but could at least make it more likely that Americans take on a portfolio of initiatives and still return home with a reliable benefits package.

Pilots at the state level are real-time tests of the positive individual, communal, and economic benefits of policies aligned with the freedom to work. Utah prohibits state agencies from weighing whether an employer provides benefits to a worker as a factor in determining whether that worker is an employee. [54] This frees employers to offer unique benefits packages to part-time or seasonal workers without incurring the sorts of responsibilities and obligations that commonly attach to an employer-employee relationship. Americans would benefit from additional experimentation around how best to structure and encourage bespoke employer-worker arrangements that do not force workers to alter how they perform their work nor for whom based on concerns around benefits.

Congressional leadership on the freedom to work is especially necessary in the Age of AI because workers and employers alike are unsure of which jobs, products, goods and services are likely to be profitable over the long term. Advances in AI do not impact all tasks and, therefore, all jobs equally. The so-called “jagged frontier” of AI is a reflection of its uneven and uncertain pace of development in different domains. Professions deemed to have less exposure to AI today because existing systems have yet to reliably and accurately perform tasks typical of that job may not be as “AI proof” tomorrow. AI labs have yet to determine a clear path for AI capability development. The task of predicting which AI models can do what may become even harder in the near future as labs pursue novel training strategies and explore new AI architectures.

In this environment, as hinted at above, a worker keen to get ahead of AI may want to simultaneously hold several jobs. They may spend half of their time with a traditional employer, thirty percent on an Etsy-based knitting business, and the remaining twenty percent as an independent contractor for a party-planning company during the summer and for a ski photography outfit in the winter. Policies that further the freedom to work will ease and even encourage such a work portfolio.

* * *

The freedom to study, shadow, and work—collectively, Entrepreneurial Liberty—was necessary long before ChatGPT found its way into our lives. The diffusion of AI has simply made the systemic barriers that have long characterized and hindered education, apprenticeships, and flexible work arrangements more apparent. Now Congress must take steps to remove barriers to those freedoms and empower individuals to chase and attain the American Dream.

[1] Huileng Tan, Young people aren't getting hired — but AI isn't to blame, an economist says, Business Insider, 2025.

https://www.businessinsider.co...

[2] James Truslow Adams, The Epic of America, Little, Brown and Company, 1931.

[3] Robert D. Atkinson & John Wu, False Alarmism: Technological Disruption and the U.S. Labor Market, 1850–2015, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2017.

https://itif.org/publications/...

[4] Timothy B. Lee, Driverless trucks are coming and unions aren’t happy about it, Understanding AI, 2025. https://www.understandingai.or...

[5] Huileng Tan, Young people aren't getting hired — but AI isn't to blame, an economist says, Business Insider, 2025.

https://www.businessinsider.co...

[6] Daniel Mark Deibler, Competition and Contracting: The Effect of Competition Shocks on Alternative Work Arrangements in the U.S. Labor Market, U.S. Department of Labor, 2018.

https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolg...

[7] Peter Cappelli, Old Laws Hobble the New Economy Workplace, MIT Sloan Management Review, 2001.

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/ar...

[8] Kevin Carey, The Problem With “In Demand” Jobs, The Atlantic, 2024.

https://www.theatlantic.com/id...

[9] Ajay Agrawal & Joshua S. Gans, Transformative AI and the Increase in Returns to Experimentation: Policy Implications, The Digitalist Papers, 2025.

https://www.digitalistpapers.com/vol2/agrawalgans.

[10] Joel Dickson, What to know about the new Trump accounts for kids, Vanguard, 2026.

https://corporate.vanguard.com...

[11] James Truslow Adams, The Epic of America, Little, Brown and Company, 1931.

[12] Trump Accounts Will Chart the Path to Prosperity for a Generation of American Kids, White House, 2025.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/art...

[13] Daniel Béland, The Ownership Society in Comparative Perspective, Policy Studies Journal, 2007.

[14] Exploring the Concept of an “Ownership Society”, NPR, 2005.

https://www.npr.org/2005/01/24...

[15] President George W. Bush, National Homeownership Month, White House Archives, 2005.

https://georgewbush-whitehouse...

[16] Heather Wilson, Economic Security and Mobility: Reviving the American Dream, National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023.

https://www.ncsl.org/human-ser...

[17] Seth Moulton, Building Economic Security, U.S. House of Representatives, 2025.

https://moulton.house.gov/issu...

[18] Justin T. Callais et al., Social Mobility in the States, Archbridge Institute, 2025.

https://www.archbridgeinstitut...

[19] Gabriel Borelli, Americans are split over the state of the American dream, Pew Research Center, 2024.

https://www.pewresearch.org/sh...

[20] The American Dream is Fading, Opportunity Insights, 2025.

https://opportunityinsights.or...

[21] Richard Fry, The shares of young adults living with parents vary widely across the U.S., Pew Research Center, 2025.

https://www.pewresearch.org/sh...

[22] Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2024, Federal Reserve, 2025.

https://www.federalreserve.gov...

[23] Yann LeCun, Advice for young students wanting to go into AI, Business Insider, 2025.

https://www.businessinsider.co...

[24] David M. Quinn & Morgan Polikoff, Summer learning loss: What is it, and what can we do about it?, Brookings Institution, 2017.

https://www.brookings.edu/arti...

[25] Aliza Chasan, How schools' long summer breaks started, CBS News, 2024.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/w...

[26] Kara Arundel, 3 things to know about school choice in the “One Big, Beautiful Bill”, K-12 Dive, 2025.

https://www.k12dive.com/news/3...

[27] Jill Anderson, School Vouchers Explained, Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2025.

https://www.gse.harvard.edu/id...

[28] James Pethokoukis, Actually, We Shouldn’t Keep All Students in High School Until They’re 18, American Enterprise Institute, 2012.

https://www.aei.org/education/...

[29] Sierra Latham, What happens to teens who leave high school and work, Urban Institute, 2016.

https://www.urban.org/urban-wi...

[30] Brian Rosenberg, Higher Ed’s Ruinous Resistance to Change, Chronicle of Higher Education, 2023.

https://www.chronicle.com/arti...

[31] Greg Ferenstein, How history explains America’s struggle to revive apprenticeships, Brookings Institution, 2018.

https://www.brookings.edu/arti...

[32] Alexander Mayer, Workforce Pell can lead to good jobs for students, Hechinger Report, 2025.

https://hechingerreport.org/op...

[33] Te-Ping Chen, The Schools Reviving Shop Class Offer a Hedge Against the AI Future, Wall Street Journal, 2025.

https://www.wsj.com/us-news/ed...

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] P-TECH 9-14 School Model, IBM, 2025.

https://www.nga.org/wp-content...

[37] Curran McSwigan & Frank Avery, What Five Countries Can Teach America About Apprenticeships, Third Way, 2025.

https://www.thirdway.org/repor...

[38] A Policy Agenda for a Skills-Based Labor Market in the AI Era, Opportunity@Work, 2025.

https://cdn.prod.website-files...

[39] Richard R. Smith & Arafat Kabir, AI Means the End of Entry-Level Jobs, Wall Street Journal, 2025.

https://www.wsj.com/opinion/ai...

[40] Seth Yudof, The Career Ladder Just Got Terminated, Rolling Stone, 2025.

https://www.rollingstone.com/c...

[41] Matt Perez, Law Firms' Junior Roles At Risk From AI, Law360, 2025.

https://www.law360.com/pulse/a...

[42] Daniel Kuehn et al., Do Employers Earn Positive Returns to Investment in Apprenticeships?, U.S. Department of Labor, 2022.

https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolg...

[43] Stephen F. Hamilton et al., Mentoring in Practice, Urban Institute, 2022.

https://www.urban.org/sites/de...

[44] Kelly Field, The US wants more apprenticeships. The UK figured out how, Hechinger Report, 2025.

https://hechingerreport.org/us...

[45] James W. Ely, Jr., Economic Liberties and the Original Meaning of the Constitution, San Diego Law Review, 2007.

[46] John C. Pinheiro, The Roots of Jefferson's Union, Law & Liberty, 2024.

https://lawliberty.org/the-roo...

[47] Vanessa Brown Calder, The Future of Working Parents, Cato Institute, 2022.

https://www.cato.org/blog/futu...

[48] C. Jarrett Dieterle, Ending the Independent Contractor Debate, R Street Institute, 2025.

https://www.rstreet.org/commen...

[49] Id.

[50] How the Complexity of the Tax Code Hinders Small Businesses, NASE, 2025.

https://www.nase.org/news/2009...

[51] Senator Bill Cassidy, Portable Benefits: Paving the Way Toward a Better Deal for Independent Workers, U.S. Senate HELP Committee, 2025.

https://www.help.senate.gov/im...

[52] Michael Schrage, Just How Valuable Is Google’s “20% Time”?, Harvard Business Review, 2013.

https://hbr.org/2013/08/just-h...

[53] Id.

[54] Liya Palagashvili, Flexible Benefits for a Flexible Workforce, Mercatus Center, 2024.