Ready for Patenting? A Debate on the Intended Purpose of an Invention

Yuqing Cui

Yuqing Cui is a 3L at Harvard Law School. She obtained her Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from MIT in 2016. Special thanks to Dr. Ryan Petty for his helpful comments and insight.

Recommended Citation

Yuqing Cui, Case Comment, Ready for Patenting? A Debate on the Intended Purpose of an Invention, Harv. J.L. & Tech. Dig. (2019), https://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/ready-for-patenting-a-debate-on-the-intended-purpose-of-an-invention.

The Federal Circuit recently engaged in a detailed discussion on the legal standard of experimental-use as a negation of the public-use statutory bars in Barry v. Medtronic, Inc.[1] In her dissent, Chief Judge Prost proposed several readings of the precedent different from those of the majority on the experimental-use and "ready for patenting" doctrines. This Comment evaluates these proposals, and thus discusses only the facts and legal analysis related to those doctrines.

The patents-in-suit, U.S. Patent Nos. 7,670,358 and 8,361,121, claim methods and systems for correcting spinal column anomalies, such as scoliosis, by applying force through a derotation tool to multiple vertebrae at once.[2] Dr. Mark Barry, a medical surgeon, was the sole inventor of the two patents. One of the key issues in this case concerns the timing of the use of the invention relative to the patent application filing. Section 102(b) of the Patent Act bars patenting of inventions already in "public use" in the United States for more than one year before the patent application was filed.[3] Thus, one year prior to the filing date (or priority date) is known as the critical date. Dr. Barry had produced a derotation tool allowing for spinal correction by July 2003.[4] He subsequently used the invention in three surgeries treating three different types of common spinal column conditions, all of which took place before the critical date.[5] After a three-month acute phase of recovery, patients from each surgery returned to Dr. Barry for follow-up appointments so Dr. Barry could determine if the scoliosis had been successfully corrected by the surgeries.[6] Two of the three-month follow-ups took place prior to the critical date, but the follow-up of the last surgery occurred after the critical date.[7] Dr. Barry testified that only after that last three-month follow-up was he confident that the invention would work for its intended purposes.[8]

Dr. Barry sued Medtronic, who produced and instructed use of a similar surgical tool, for infringement in the Eastern District of Texas. The jury delivered a verdict for Dr. Barry, including that the invention was not in public use before the critical date.[9] The district court denied Medtronic’s post-trial motion for judgment as a matter of law that the patents were invalid under § 102(b).[10] Medtronic appealed this decision for the ’358 patent.[11]

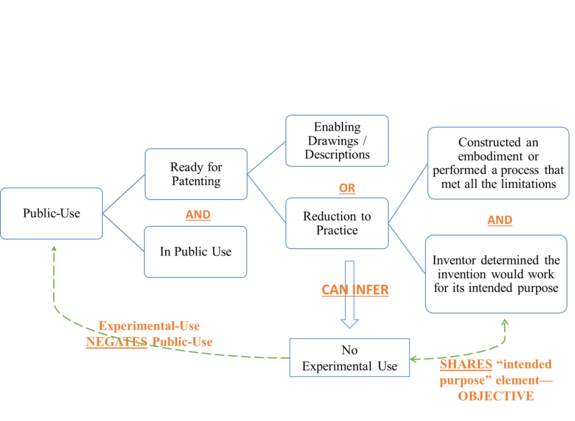

The majority, in an opinion by Judge Taranto, affirmed the district court’s decision.[12] It concluded the patent was not barred for invalidating public-use because the invention was not ready for patenting before the critical date and relatedly there was no public-use except for experimental-use, which can act as a negation of the public-use bar.[13] The legal standards applicable here have multiple layers. To trigger the § 102(b) public-use bar, the claimed invention, before the critical date, must have been 1) in public use and 2) ready for patenting.[14] Readiness for patenting can be shown by 1) a reduction to practice or, 2) drawings or descriptions enabling an ordinarily skilled artisan to practice the invention.[15] For reduction-to-practice, the challenger must show that "the inventor (1) constructed an embodiment or performed a process that met all the limitations and (2) determined that the invention would work for its intended purpose."[16] Figure 1 illustrates the applicable legal standards. The Barry majority held that the jury could have reasonably found the invention was not reduced to practice before the critical date by accepting Dr. Barry’s testimony that he was not confident the invention worked for its "intended purpose" until the last three-month follow-up of the three surgeries.[17] As such, any public use before the critical date was negated by experimental-use which shares the same "intended purpose" element as the "reduction to practice" inquiry. Although the only evidence supporting experimental-use is Dr. Barry and his expert’s testimony, the majority seems to have given Dr. Barry the benefit of the doubt because the underlying facts are reviewed for substantial evidence following a jury verdict.[18]

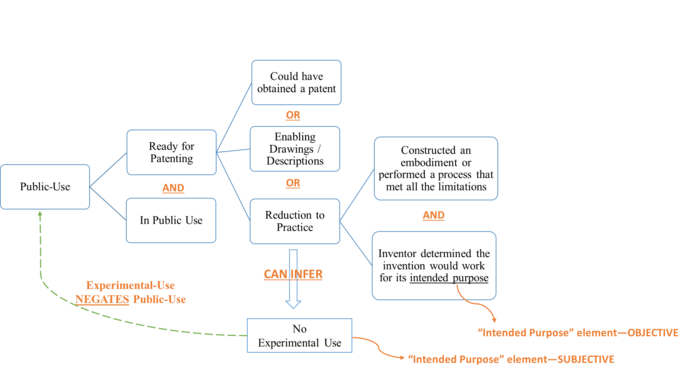

Chief Judge Prost dissented in part, disagreeing with the majority’s analysis on public-use and experimental-use.[19] Specifically, Judge Prost proposed what she believed to be the correct understanding of three legal doctrines.[20] First, instead of adhering to the traditional two-element test of "ready for patenting," Prost proposed a third, broader test asking "whether the inventor could have obtained a patent."[21] Chief Judge Prost derived this test from the Supreme Court’s precedent Pfaff v. Wells Elecs.[22] In its determination that the invention was ready for patenting in Pfaff, the Supreme Court stated that the patentee "could have obtained a patent."[23] However, the Court used this language to support the traditional test for "ready for patenting" that the patentee provided enabling "description and drawings."[24] Thus, the Supreme Court did not appear to have intended to establish "could have obtained a patent" as a third test in addition to the two it announced in Pfaff.

Chief Judge Prost next proposed to read the intended purpose of the invention narrowly and quite literally based on patent claims and specifications. The claims of the ’385 patent defined the intended purpose as "the amelioration of aberrant spinal column deviation conditions."[25] The dissent faults the majority for improperly expanding the scope of the intended purpose to include more permanent amelioration that lasts until the three-month follow-up, and to include working across three different types of conditions, neither of which was not explicitly recited in the claims or specification.[26] Chief Judge Prost advocates an objective, literal patent-based reading of the intended purpose such that any amelioration observed immediately at a surgery’s completion fulfills the stated intended purpose.[27] When the court and jury have to look outside the patent to determine the intended purpose of the invention, Chief Judge Prost suggests that such determination could be arbitrary: for example, while Dr. Barry believed three months were necessary as follow-up time to determine the efficacy of the surgery, his expert testified that peer-reviewed publications require two years’ follow-up time.[28] And just how many types of conditions does the invention need to treat to fulfill its "intended purpose," two, three, ten?[29] While this is a legitimate concern, Chief Judge Prost appears to be invading the province of the jury here, because, as she stated, "the testing necessary to determine whether an invention would work for its intended purpose is a factual question."[30] The court may only define the intended purpose of the patent, and on that front, the majority and dissent agree that it is "the amelioration of aberrant spinal column deviation conditions."[31] The actual determination of whether the invention would work for its intended purpose should be left to the jury.

Finally, Chief Judge Prost proposed to eliminate the subjective inquiry into the "intended purpose" element for determining "reduction to practice."[32] The "intended purpose" element exists in both the "reduction to practice" and the "experimental-use" determinations. Chief Judge Prost suggested the "intended purpose" element has to be construed differently so the two inquiries are not superfluous to each other.[33] She explained that experimental use focuses on the inventor’s intent and is thus subjective, while the "reduction to practice" inquiry relates to how far along the invention is in terms of reduction to practice and should thus be objective.[34] This interpretation seems to be at odds with the Federal Circuit’s own precedents that have intricately linked "reduction to practice" with "experimental-use" using a subjective standard.[35] In addition, the policy objective of the public-use bar coupled with the experimental-use exception is to allow inventors to experiment and perfect their inventions while encouraging them to apply for patents as soon as the experiments conclude. If an inventor does not subjectively believe the invention has been reduced to practice, the objective determination that it has will not help or incentivize the inventor to submit the patent application. Taken together, Chief Judge Prost’s reading of the law can be summarized in Figure 2.

As the majority points out, Judge Prost’s approach does not follow "existing case law,"[36] which uses the traditional two-prong test to determine "ready for patenting" laid out in Pfaff and the same subjective "intended purpose" determination in both "reduction to practice" and experimental-use. This test ultimately provides a proper balance between incentivizing the inventor to affirm the utility of their invention with incentivizing them to file their patent as soon as practicable.

[1] 914 F.3d 1310, No. 2017-2463 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 24, 2019). The experimental-use exception applies similarly to the on-sale statutory bar. See id., Majority op. at 32 ("[E]xperimental use negates applicability of the on-sale bar, as it does the public-use bar." (citing Polara Eng’g Inc v. Campbell Co., 894 F.3d 1339, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2018)).

[2] Barry, Majority op. at 2.

[3] 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) (2002). The patents at issue are subject to pre-AIA law. Barry, Majority op. at 8–9 n.1.

[4] Barry, Majority op. at 7–8.

[5] Id. at 8.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id. at 9; Barry v. Medtronic, Inc., 230 F. Supp. 3d 630, 637 (E.D. Tex. 2017).

[10] 230 F. Supp. 3d at 654–56.

[11] Barry, Majority op. at 2–3.

[12] Id. at 3.

[13] Id. at 11.

[14] Id.

[15] Id. at 13.

[16] Id. at 14 (quoting In re Omeprazole Patent Litig., 536 F.3d 1361, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2008)).

[17] Id. at 8.

[18] Id. at 17 (stating that Dr. Barry’s and his expert’s testimony that at least three months of follow-up is consistent with standards for peer-reviewed publications reporting new techniques "suffices for the jury to have rejected Medtronic’s contention that Dr. Barry is charged with knowing that the surgical technique worked for its intended purpose immediately upon completion of the surgical operation.").

[19] Barry, Dissent op. at 1.

[20] Id. at 2.

[21] Id. at 7–8 (quoting Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55, 67–68 (1998)).

[22] 525 U.S. 55 (1998).

[23] Id. at 63.

[24] Id.

[25] ’385 Patent col. 6 ll. 7–8.

[26] Barry, Dissent op. at 10–13.

[27] Id. at 11–12

[28] Barry, Dissent op. at 10 n.4.

[29] Id. at 13 ("I . . . fail to understand the legal relevance of Dr. Barry’s alleged need for the third surgery’s follow-up, as opposed to just the first two, to determine whether his invention worked for its intended purpose[.]").

[30] Id. at 10.

[31] Id.

[32] Id. at 14–15.

[33] Id. at 14.

[34] Id. at 15.

[35] See, e.g., In re Cygnus Telecommunications Technology, LLC, Patent Litigation, 536 F.3d 1343, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (affirming district court’s ruling of no experimental-use based on Federal Circuit’s law that "experimental use cannot occur after a reduction to practice"; reduction to practice was shown by patentee’s own testimony of subjective understanding); In re Omeprazole Patent Litigation, 536 F.3d at 1372 ("[I]t is clear from this court's case law that experimental use cannot negate a public use when it is shown that the invention was reduced to practice before the experimental use.") (citations omitted); Cargill, Inc. v. Canbra Foods, Ltd., 476 F.3d 1359, 1371 n.10 (Fed. Cir. 2007) ("[O]nce the invention is reduced to practice, there can be no experimental use negation.") (alteration in original) (citations omitted).

[36] Barry, Majority op. at 12 n.3.