A Double-Patenting Double Whammy: Federal Circuit Addresses Impact of the Uruguay Rounds Agreement Act and Patent Term Extension on Obviousness-Type Double Patenting

Ryan V. Petty, Ph.D

J.D., Harvard Law School, Class of 2019 (expected); Ph.D., Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2014. Many thanks to Kee Young Lee for his insightful comments and invaluable edits. Additional thanks to the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology Digest for spearheading the new Federal Circuit Panel Case Comments.

Recommended Citation

Ryan V. Petty, Case Comment, A Double-Patenting Double Whammy: Federal Circuit Addresses Impact of the Uruguay Rounds, Harv. J.L. & Tech. Dig. (2019), https://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/double-patenting-double-whammy.

Patentability requires that an invention be new, useful, and non-obvious. Should an invention satisfy these requirements, the inventor is entitled one patent.[1] Courts have enforced this restriction by invalidating attempts by inventors to obtain multiple patents for the exact same invention—statutory double patenting—and by rejecting obvious variants of an invention—obviousness-type double patenting ("OTDP"). OTDP is "a judicially-created doctrine grounded in public policy rather than statute" and is designed, in part, to prevent inventors from obtaining an unjust extension of their time-limited monopoly.[2] At an earlier time when patent expiration dates were tied to their issuance dates, patentees could, in theory, manipulate the issue dates of patentably indistinct claims to obtain the longest possible term of protection. OTDP was designed by courts to prevent this sort of "gamesmanship" by patentees.[3] Under a traditional OTDP scenario, a later-issued, later-expiring patent would have its term truncated to match that of an earlier-issued, earlier-expiring patent if the later patent was an obvious variant of the earlier.[4] Left unresolved, however, was the interaction of OTDP with several intervening Congressional acts that explicitly granted patentees longer terms.

In a pair of cases—Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharmpharmaceutical, Inc.[5] and Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC[6]—argued on consecutive days and decided on the same day,[7] the Federal Circuit clarified the interaction of OTDP with two of these patent term-modifying laws—the Uruguay Round Agreements Act ("URAA")[8] and the Patent Term Extension ("PTE") provision of the Hatch-Waxman Act,[9] respectively. The URAA alters the expiration date of patents from 17 years post-issuance to 20 years post-effective filing date, and ensures patents in force or filed within 6 months of URAA implementation the longer of the two terms, whereas PTE compensates for delays in obtaining regulatory review, often for pharmaceuticals.

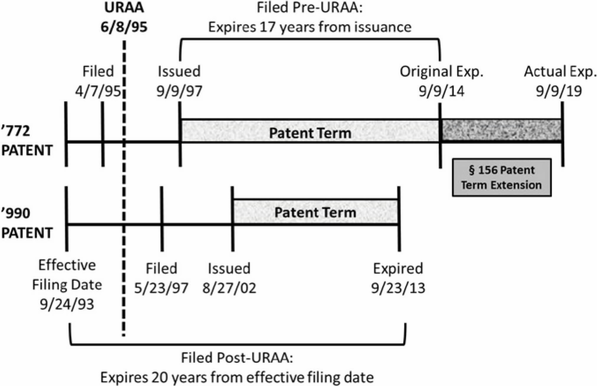

Beginning with Breckenridge and the URAA, Novartis owned two patents, the '772[10] and '990.[11] The '772 patent claims the compound everolimus whereas the '990 patent claims methods of administering everolimus. The '772 was filed before the '990, though both patents claim the same priority date of September 24, 1993.[12] Because the '772 was filed before the URAA, it was entitled to the longer of 17 years post-issuance or 20 years post-effective filing date.[13] The '990 was filed after the URAA and therefore only entitled to a term of 20 years post-effective filing date.[14] As a result, the '772 expired after the '990, despite being filed earlier.[15] These dates are summarized in Figure 1.[16]

Figure 1.

In the background of Breckenridge was a prior decision, Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd.,[17] that held that a patent that issues after but expires before another patent may serve as an OTDP invalidating reference, even for post-URAA patents.[18] The district court in Breckenridge had applied Gilead and found the '990 to be a proper invalidating reference against the '772.[19] Both patents in Gilead, however, were filed post-URAA with different priority dates, unlike the pre-/post-URAA split and common priority date in Breckenridge.[20] The Breckenridge panel, in a unanimous opinion by Judge Chen, acknowledged this distinction and reversed the district court.[21] The Breckenridge court noted that the terms of the two patents were different exclusively due to the URAA, an intervening act of Congress.[22] Congress’s directive in ensuring patents filed pre-URAA the greater of the two possible expiration dates was evidence that patentees should enjoy the "maximum possible term available."[23] That both the '990 and '772 claimed priority to the same pre-URAA date evidenced a lack of gamesmanship on the part of Novartis.[24] Moreover, the traditional OTDP scenario of a later-issuing, later-expiring patent was absent here.[25] Therefore, the post-URAA patent was not a proper OTDP invalidating reference against the pre-URAA patent.[26] Notably, the URAA had not extended the term of the earlier-filed '772 patent; it actually truncated the term of the later-filed '990 patent.[27] The court acknowledged that different fact patterns could arise with pre- and post-URAA patents, and expressly limited its opinion to the facts before it.[28]

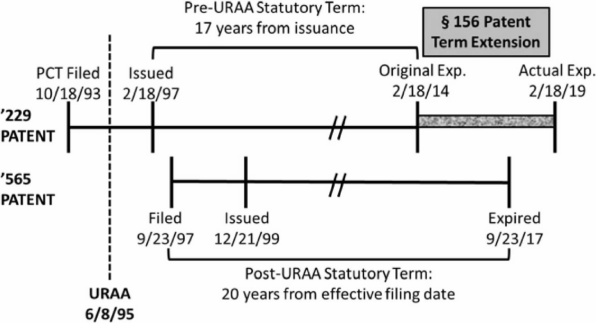

Figure 2.

In the second case, Ezra, Novartis owned two patents, the '229[29] and '565.[30] The '229 patent claims the compound fingolimod whereas the '565 claims a method of administering fingolimod. The '229 was filed and issued before the '565 was even filed. The '229 was filed pre-URAA, and its 17-year post-issuance term would have ended prior to expiration of the '565. However, Novartis chose to apply the statutory maximum five years of PTE to the '229, such that the '229 expired after the '565. These dates are summarized in Figure 2.[31]

Ezra filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application for fingolimod and was sued by Novartis for infringement. In response, Ezra argued that Novartis’s application of PTE to the '229 patent effectively extended the life of the '565 patent and, therefore, the '565 was a proper OTDP reference against the '229.[32] Central to Ezra’s argument was the text of the relevant statutory provision governing PTE that states "in no event shall more than one patent be extended under [PTE] for the same regulatory review period for any product."[33] The Ezra panel, in a unanimous opinion also by Judge Chen, began its analysis by noting that "nothing in the statute restricts the patent owner’s choice for patent term extension among those patents whose terms have been partially consumed by the regulatory review process."[34] The panel affirmed the district court’s rejection of Ezra’s attempts to read the word "effectively" before the word "extended" into the PTE provision.[35] Instead, as the Ezra court asserted, the relevant language limiting PTE to one patent selected by the patentee was intended to do so de jure, not de facto.[36] This holding was supported by a prior ruling in Merck & Co., Inc. v. Hi-Tec Pharmacal Co., Inc.,[37] where the Federal Circuit held that Congress explicitly gave patentees the choice of which patent’s term to extend without any practical limitation.[38] By contrasting the language in the Patent Term Adjustment ("PTA") provision[39] that expressly limits PTA for patents subject to terminal disclaimers—a remedy to overcome OTDP rejections and invalidations—with the absence of such qualifying language in the PTE provision, the Merck court concluded that Congress intended that patentees should get their full term under PTE, even in the face of OTDP rejections.[40] The outcome in Ezra was a natural consequence of Merck’s holding.[41] Simply put, there can be no gamesmanship penalized by the courts when Congress has concretely dictated the outcome.

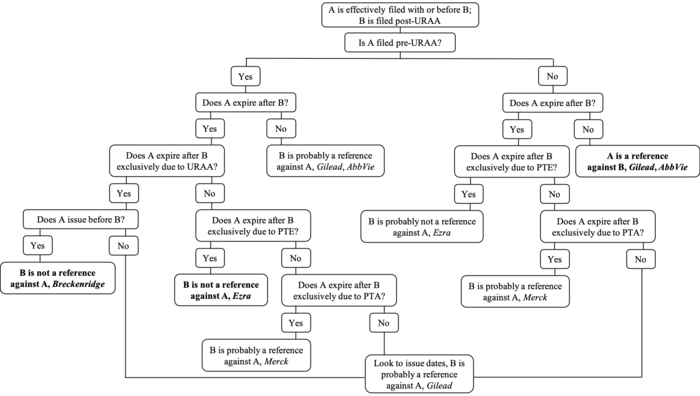

The impact of the URAA on OTDP will eventually be relegated to history as patents granted pre-URAA expire and the expiration date of all extant patents are tied to their effective filing date. For the time being, though, the Federal Circuit continues to clarify the impact of Congressional actions like the URAA and PTE on its judge-made doctrine. The current state of OTDP when at least one patent is filed post-URAA is summarized in Figure 3, with bold text indicating explicitly-addressed issues.

Figure 3. Click here for higher resolution version

[1] 35 U.S.C. § 101 (". . . may obtain a patent therefor . . . ." (emphasis added)).

[2] Application of Thorington, 418 F.2d 528, 534 (C.C.P.A. 1969). OTDP also prevents multiple infringement suits from different plaintiffs over obvious variants of the same invention. See In re Van Ornum, 686 F.2d 937, 944–48 (C.C.P.A. 1982).

[3] See Gilead Sciences, Inc., v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208, 1215 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[4] See, e.g., Boehringer Ingelheim Intern. GmbH v. Barr Labs., Inc., 592 F.3d 1340, 1347; AbbVie Inc. v. Mathilda and Terence Kennedy Inst. of Rheumatology Tr., 764 F.3d 1366, 1372–74 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[5] 909 F.3d 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

[6] 909 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

[7] June 4 & 5, 2018 and Dec. 7, 2018, respectively.

[8] Pub. L. No. 103–465, 108 Stat. 4809 (1994); 35 U.S.C. § 154(c)(1) (at relevant part).

[9] Pub. L. No. 98–417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984); 35 U.S.C. § 156.

[10] U.S. Patent No. 5,665,772.

[11] U.S. Patent No. 6,440,990.

[12] 909 F.3d at 1359.

[13] Id.; see also 35 U.S.C. § 154(c)(1).

[14] 909 F.3d at 1359.

[15] Novartis also elected to extend the '772 patent five additional years under PTE. This, however, is unrelated to the expiration date issue since the '772 already expired after the '990 before PTE was applied. Id. at 1361 n.2.

[16] Id. at 1360.

[17] 753 F.3d 1208 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[18] Id. at 1212. The Federal Circuit reaffirmed Gilead in AbbVie. 764 F.3d 1366, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

[19] Novartis Pharms. Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharm., Inc., 248 F. Supp. 3d 578, 589 (D. Del. 2017).

[20] 753 F.3d at 1210. The two patents at issue in Gilead also had different effective filing dates. Id.

[21] 909 F.3d at 1360–62.

[22] Id. at 1364.

[23] Id. at 1366 ("[T]o truncate [under OTDP] any portion of the statutorily-assigned term of a pre-URAA patent that extends beyond the term of a post-URAA patent would be inconsistent with the URAA transition statute.").

[24] Id. at 1364.

[25] Id. at 1366; see also AbbVie, 764 F.3d 1366, 1372–74 (applying traditional OTDP principles to post-URAA patents).

[26] Id. at 1366–67.

[27] 909 F.3d at 1367 (noting that the 20 years post-effective filing date term of the '990 patent is shorter than what the '990 would have enjoyed had its term been 17 years post-issuance).

[28] Id. at 1366 n.3.

[29] U.S. Patent No. 5,604,229.

[30] U.S. Patent No. 6,004,565.

[31] 909 F.3d at 1370.

[32] Id. at 1370–71.

[33] 35 U.S.C. § 156(c)(4).

[34] 909 F.3d at 1372.

[35] Id. at 1372–73.

[36] Id. at 1373.

[37] 482 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

[38] Id. at 1323. This assumed the patentee met the statutory requirements in 35 U.S.C. § 156(a)–(d).

[39] Patent Term Adjustment compensates patentees for delays caused by the Patent and Trademark Office by extending the term of the affected patent. See 35 U.S.C. § 154(b).

[40] 482 F.3d at 1322 ("The express prohibition against a term adjustment regarding PTO delays, the absence of any such prohibition regarding Hatch-Waxman extensions, and the mandate in § 156 that the patent term shall be extended if the requirements enumerated in that section are met, support the conclusion that a patent term extension under § 156 is not foreclosed by a terminal disclaimer.").

[41] 909 F.3d at 1373, 1375.