Complaint for injunctive and equitable relief, ACLU v. Clearview AI Inc (Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois, May 28, 2020)(No. 9337839), complaint hosted by the ACLU.

The ACLU is suing Clearview, a facial recognition company, under the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA). The suit raises the issue of privacy as facial recognition technology grows increasingly sophisticated and ubiquitous.

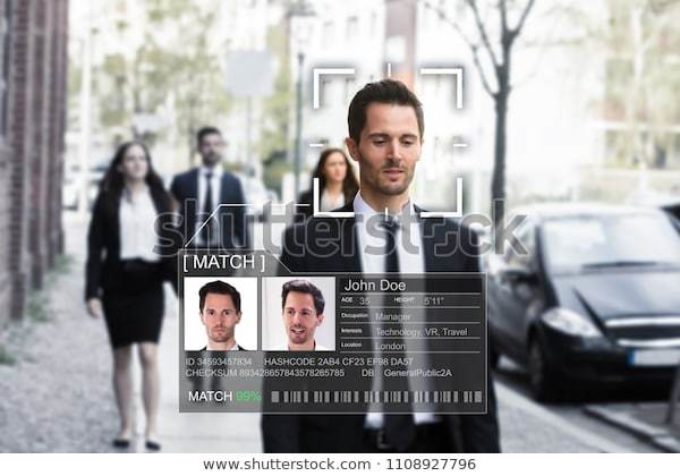

Clearview sells facial recognition services, advertising its database as the largest in the world. The company’s database consists of photos scraped from the internet—including from major social media sites, in violation of their stated policies. Users of the service can submit a person’s image—even when taken with a half-covered face, at a bad angle, or in bad lighting—and receive an identification complete with matching images and links. The technology works by making a “face-print” of the submitted image, based on the immutable geography of the individual’s face. This faceprint is then run through the database, and any matching images are flagged.

With this technology, Clearview has not broken new ground, but has taken a commercial step that companies such as Google have declined to take. In 2011, Eric Schmidt, Google’s then-CEO, shut down a Clearview-like project to build a facial recognition database, citing the “very concerning” privacy implications.

Clearview has claimed to only sell this service to law enforcement in America and Canada, but a leaked list showed clients ranging from stores like Walmart, to gyms like Equinox, to private individuals like Ashton Kutcher. Clearview has also offered 30-day free trials to individual police officers, in the hopes that these officers will convince their departments to adopt the service. The company makes no public disclosures about who is able to access its database at a given time.

The New York Times cautioned that Clearview’s facial recognition business, if left unchecked, “might end privacy as we know it.” Perfected, the system promises an end to public anonymity. The ACLU complaint warns that this broad-scale facial recognition could make it possible “to instantaneously identify everyone at a protest or political rally, a house of worship, a domestic violence shelter, an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, and more.”

The ACLU suit is limited to exploring the ways in which Clearview’s facial recognition business has violated BIPA, which forbids the nonconsensual capture of unique identifiers like the “faceprints” belonging to Illinois citizens. This state statute was enacted in 2008 after Pay by Touch, a company that provided fingerprint scanners to major retailers, went bankrupt, opening its store of millions of unique fingerprint records to sale and distribution. BIPA protects the interest that individuals have in personal identifiers which are unique and immutable. However, the law is an outlier in the current Wild West of facial recognition. While municipalities like San Francisco have banned facial recognition altogether, there are no state statutes comparable to BIPA in their biometric privacy protections. Due to BIPA’s unique nature, the court’s decision in ACLU v. Clearview will not have directly applicable consequences outside of Illinois. But for states concerned about privacy infringements on their citizens, or a federal government beginning to take note of the regulatory vacuum that is facial recognition, the case sounds a blaring alarm. Clearview’s copyright-violating image scraping, rather than privacy violations, may ultimately doom the company. But the issue of facial recognition technology will not end with Clearview. The company’s model, an enticingly simple combination of facial recognition software and opportunistic image scraping, is easily replicable. At the moment, outside of rare statutes like BIPA, little stands in the way of this mass facial surveillance other than a commonly-held understanding of privacy norms. In the absence of legislation, these norms may soon be swept aside.